There is an animal I want to talk about called the quagga (Equus quagga quagga). The quagga is difficult to talk about for a few reasons. It was a plains zebra, technically; not a species in its own right, but a subspecies. Its name is the first snag. “Quagga” is used throughout southern Africa to refer to zebras in general, as well as being the specific term for the subspecies. That’s the reason for the echo in the Latin name. When someone talks about a quagga, you have to check if they're talking about the quagga quagga, not just the quagga. The next hurdle is its existence: the quagga has been extinct for over one hundred years, and little information survives regarding what they were really like. Only one quagga specimen was ever photographed alive. We don’t know her name, just that she was a mare and lived at the London Zoo. There are just twenty-three surviving pelts. Once abundant, they have been reduced to barely a lonely memory. The quagga may as well have never existed. But it did exist. We cannot forget what we did to it. What we keep doing.

one of five surviving quagga photos

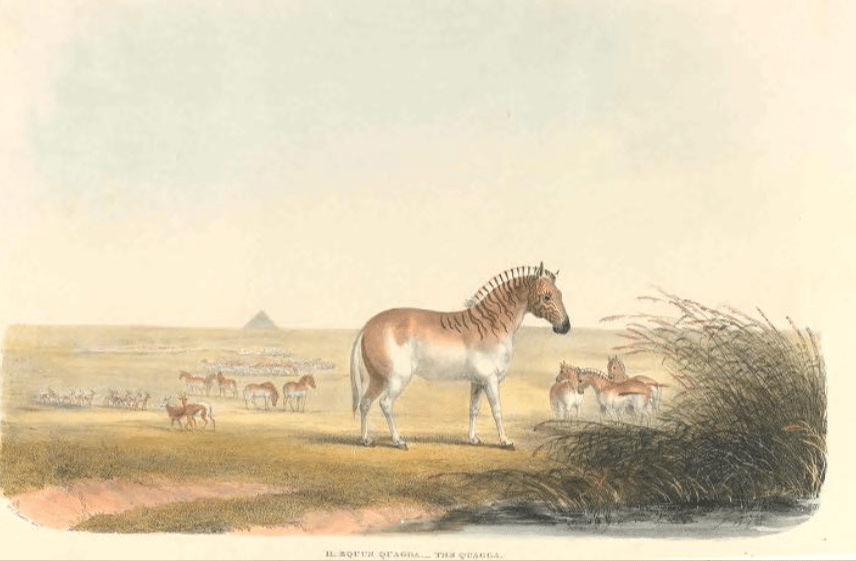

The quagga quagga was endemic to what is now called South Africa. It was distinguished from other zebras by its minimal stripes. While their head had the familiar pattern, it ended on their neck, with the rest of their body a plain brown. Some quaggas had more stripes than others; variety, after all, is the goal of evolution. They were a little larger than extant zebras, with the females being bigger than males. The fate of the quagga is eerily similar to that of the passenger pigeon, about which I have written previously. They even disappeared at a similar time, within decades of one another. Quagga were once abundant. Once Europeans settled on its land, however, they quickly began to hunt the quagga as a food source at an unsustainable rate.

I learned about quaggas early on. There was a photo—one of the photos—in an animal encyclopedia that I adored. It was the same book that gave me olms and myriad other species. When I was in Year 3, my teacher asked the class to name animal categories. Once we’d gotten the obvious ones out of the way—mammal, reptile, monotreme—I offered up “ungulate”: animals with hooves. My teacher had never heard the term before and refused to accept it as an answer. I was surprised she didn’t know, given that I, an eight-year-old, did. A lot of stories about my childhood are like that. Symptoms hidden in plain sight. I was undiagnosed, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t clear. It was always somewhere in-between.

Aside from taxonomic description, we don’t know quaggas very well. There are very few observational records from before their extinction. Frustratingly, there seems to be very little accessible material on pre-colonial human-quagga relationships. The San and the Khoikhoi, the two primary Indigenous groups from the region, undoubtedly had their own perspectives on the quagga, but I can’t tell you about them. The Dutch were more interested in quaggas as a resource than as a species; in addition to eating them, some efforts were made to domesticate them, as European horses were poorly suited to the southern African climate. One of few records of the quagga from Dutch colonists comes from Portraits of the Game and Wild Animals of Southern Africa (1840), by a bloke named William Cornwallis Harris. In addition to some extreme but unsurprising racism, Harris provides a somewhat detailed description of the quagga, alongside a sketch. Notably, he mentions that another man—one Phoebus Cockerlockie—was fatally kicked in the head by a quagga he was attempting to kill. We don’t know much at all about what quaggas thought of humans, other than a clear disdain for that particular guy. Even if they had survived, I don’t think we’d be able to know much about what they thought of humans. I can’t tell you if quaggas knew they were going extinct. They must have in some way. Quaggas lived and moved in herds of around 50, up to 80; they must have noticed that their communities were getting smaller and smaller. I wonder if it scared them. They frequently grazed alongside other prey animals, such as wildebeest and ostriches, each species alerting the others to approaching dangers. I wonder what the wildebeests and ostriches made of the disappearance of their fellows.

Quaggas’ distribution was not large; they mainly lived around the river isAngqu in the Karoo region. The conditions of Karoo compared to other parts of Africa potentially explains the divergent evolution of the quagga: the region is colder and does not have the tetse flies that encouraged the development of zebra stripes elsewhere. The loss of stripes on the quagga seems to be a passive aspect of their evolution. There’s a theory that domestic horses, too, lost stripes at some point in their evolution. The quagga as it was seen by settlers, and as we half-remember it now, was likely a midway point in evolution. The printer slowly running out of ink. Settlers must have watched the numbers dwindle in real time. The problem of the name was a factor here: by all accounts, there were plenty of other quaggas further to the north. And there were, technically. Just not quagga quaggas. The last captive quagga died in 1883. The last known wild one had died five years earlier, in 1878. Unlike Martha the passenger pigeon, we know very little about the quagga’s endling. Like Martha, the remains of the endling have been preserved and intermittently displayed. A necromantic monument to negligence.

Despite the taxonomic confusion, it evidently didn’t take humans that long to notice that the semi-striped zebra variety had disappeared. Henry Anderson Bryden, an Englishman writing in 1889, eulogised the quagga in Kloof and Karroo: Sport, Legend and Natural History in Cape Colony. He made no attempt to disguise the cause of the extinction; as he puts it, “The downfall of the quagga first began, as it ended, at the hands of the Boers.” Bryden doesn’t seem to be a fan of Dutch colonists in general, based on the tone of his writing. I hesitate to go as far as to say he was a paragon of modern morality in the African colonies—he still considers colonisation as a net good for everyone involved—but we certainly should have taken more cues from him than we did. I was delighted to find that he derisively refers to the Dutch as “primitive” in their approach to their newly colonised territory. Bryden is clearly disturbed by the extinction, as well he should be. He seems to be among the first to notice what it meant, both in the short- and long-term.

illustration of a quagga herd in Portraits of the Game and Wild Animals of Southern Africa (1840)

It’s misleading to say that humans drove the quagga to extinction. Humans, after all, lived alongside the quagga for thousands of years. The Bantu empire rose and fell, and the quagga remained. It is also misleading to characterise colonialism as a matter of villain and victim. It is not a framing that serves anyone, let alone the groups who got the short end of the stick. Still, it is undeniable that colonialism was a violent, destructive force unlike any other previous human endeavour. Even in previous instances of invasion and occupation, there was no such immense impact on the environment itself; not on the scale of the fifteenth century onwards. By many metrics, colonialism is the worst thing to ever happen to the planet and its species. For the quagga quagga, this was certainly the case.

There are few things I find more frustrating than hitting the limits of what we can know. It's human nature to reach for meaning; my nature, particularly, to do that through taking in as much raw information as possible. It’s why I do the things I do, and know the things I know. Now, in writing this, I’m trying to reach out to the quagga. If I just think hard enough, maybe I can imagine the feel of its fur, the exact gait with which it trotted across the savannah. I can’t imagine it accurately, of course. I must remember not to mistake my imagination for knowledge. It’s a lesson learned the hard way; the two have a habit of blurring. There’s no real way to overcome the limit of what we don’t know.

Again, like the passenger pigeon, I’m disquieted by attempts to genetically engineer the quagga back into existence. It would be easy enough to believe, I suppose. The little we know about the quagga’s behaviour makes it all the simpler to look at what we have cobbled together and imagine that it is the real thing. More than an attempt to play God, it’s an attempt at time travel. It's an abject inability to live with the consequences of our actions and learn from them. Why learn anything when you can create a replacement for what you have destroyed and convince yourself that it is no different? Bryden, in 1889, lamented, “Although easy enough to destroy, no human skill can ever restore it to its natural haunts.” Over one hundred years later, he’s still right. We can never get back the quagga quagga. “It is gone for ever,” Bryden says, “after an existence of untold thousands of years upon its spacious plains.”

Bryden’s last words on the quagga are nauseatingly prophetic. “Never more, alas ! will this fleet and handsome creature scour its primeval karroos, or proudly pace in regular formation, or with its fellows wheel and charge like a regiment of cavalry. It has been the first of the matchless fauna of South Africa to disappear. That its extinction may serve as some sort of warning to wanton and ruthless destroyers of game, whether Boer or British, or of any other nationality, is devoutly to be hoped.”

It didn’t.

The quagga is, ultimately, a footnote in natural history. Not even a species in its own right, so little about it preserved before its death. Its ambiguity—the confusion of quagga and quagga quagga—characterised its existence, as well as its end. For a period after its demise, few were willing to accept the possibility that they had been wiped out. Always, always, it was theorised there would be more. How little has changed. We can never quite seem to accept how quickly we humans—we colonists—can destroy abundance. It seems trite to characterise settlers as an invasive species, but on an ecological level, the comparison is apt. A sudden influx of population, not suited to the habitat, disrupting the delicate balance of ecology. I am far from the first person to draw the connection between the colonial period and the advent of the anthropocene, but it cannot be overstated. A great shift in human population—through both migration and genocide—naturally impacts every other creature. Most people seem to resist fully internalising that we are animals. I’ve never quite understood it, as it’s something that I have always found grounding. We are not apart from nature, but within it. Colonisation presents the same problem as cod overpopulating a lake. One species benefits in the short term, and others are destroyed. The quagga’s ambiguity made it an easy early victim. We are beginning to run out of easy victims.

The problem, I must emphasise, is not one of population numbers. It would be exceptionally inconsistent to lament the ecological consequences of African colonisation only to end up with the same line as the most famous, most boorish living Boer. The overpopulation line is at best inaccurate, and at worst fosters consent to genocide. The problem is not numbers, but balance. Humans have their place in the natural order, even in vast numbers. Distinct to our position is self-awareness, at least, when we allow it. The wildebeest and ostriches may have noticed the quagga declining, but they couldn’t adjust their own behaviour to change that. We, however, can. The quagga’s extinction was the result of human decision; many, collectively, leading to decimation. Ecological destruction, however vast, is a matter of choice. The solution requires re-organisation. It is not an easy task, but there is also no task more important. Our approach to our landscapes must be led by those who understand it, not those who seek to dominate it. The latter is the paradigm set in place by colonisation. It is a norm so vast that it seems impossible to change; but, as Ursula Le Guin reminds us, so was the divine right of kings. Quagga quagga lived in Africa for hundreds of thousands of years. The Scramble for Africa began less than two hundred years ago. It is too late to save the quagga quagga. It is not too late for the rest. Climate fatalism is not an honest reflection of reality; by all scientific accounts, there is still time. Colonisation is the biggest event to happen in pan-human history, but it does not have to be the last. We are, at present, in-between epochs, in our own point of ambiguity. We have a choice to make, and ignoring that we have a choice is the same as making it.

so it goes