(a quick note up top, this post has quite a few pictures of underwater creatures, and also talks a fair bit about PTSD. do what ya need to.)

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about PTSD, which means I’m thinking a lot about Slaughterhouse Five. Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time. Vonnegut presents the most elegant metaphor for PTSD that I've seen because he understands that the fundamental issue of the condition is temporality. PTSD is about being abandoned by time. You never exist fully in the present moment, or in the past moment, but somewhere in-between the two. This temporal disruption is what makes the condition so difficult and distressing. Your feet are never quite on the ground. You move forward the same event is happening around you. In Slaughter-House Five, the alien species Tralfamadorians are able to move through time freely, perceiving every moment as occurring more or less simultaneously in their fourth dimension. This non-linearity means that no one ever truly dies. If you miss someone, you can easily return to a moment in which they were alive. Everyone becomes immortal.

For all the diverse and unlikely taxonomies found on our planet, no organism seems to have cracked time travel. Certain organisms can live for a very, very long time. I’ve written about the Greenland shark previously, and in 2022 I took a detour to Utah during my PhD fieldwork to visit the Pando, a grove of aspen trees that is not only one of the largest single organisms on the planet, but also one of the oldest, at least 16,000 years. There are also species that sleep for centuries at a time, which is arguably a kind of time travel, in the sense that we are all slowly doing time travel. Certain spores and bacteria preserved in salt, amber or ice have been revived after thousands of years of dormancy. It’s the Futurama version of time travel. The only animal—the only organism—that can travel through time in a non-linear fashion is the immortal jellyfish (Turritopsis dohrnii).

a look at our guy (Yiming Chen, Getty Images)

Turritopsis dohrnii appears to be utterly unique in that it does not age. They are an example of fabled biological immortality, able to revert back to its youngest, polyp state at will. Reversion can happen at any point in its life cycle and may occur indefinitely. It does not decay, and so time ceases to matter to it. I’m not actually terribly confident that time matters to any jellyfish. They lack certain significant contributors, such as a brain. They’re collections of cells that float through the ocean. A lack of survival instincts doesn’t prevent survival, it just means that you must find a particular niche. Turritopsis dohrnii isn’t the only animal with apparent biological immortality. Hydras, an almost microscopic genus, are able to regenerate indefinitely and produce asexually, and don’t seem to degrade over time at all. Hydras also live in the water. The more I read about aquatic organisms, the less confident I am that leaving the water was the groundbreaking evolutionary move we all think it was.

We’ve only ever observed Turritopsis dohrnii regenerate in laboratory environments. In nature, it’s too quick and too small to properly capture. The mature Turritopsis dohrnii is teeny tiny - not even a centimetre across. In its younger form, they’re barely a millimetre. It’s a wonder we ever noticed them at all, let alone their particular miracle. Its tiny size has been critical to its success: though it originated in the Pacific Ocean, Turritopsis dohrnii is now found in every temperate and tropical oceans across the globe. This spread is recent but merciful: Turritopsis dohrnii’s presence doesn’t seem to disrupt much in the established ecosystems.

Biological immortality can only occur in circumstances of simplicity. Turritopsis dohrnii is tiny and, no offence, not especially complex. They don’t have brains. They do have a nervous system, because they must hunt for food. They prey on zooplankton, the microscopic life forms that fill the space between water in the oceans. Turritopsis dohrnii’s life is fairly uncomplicated. They feed, and they float, and every so often they travel back in time so they can continue to feed or float indefinitely. They intend none of this: it’s simply what they do. Turritopsis dohrnii is not unstuck in time because it was never positioned there to begin with. There is no decay with which it could measure itself. Most of Turritopsis dohrnii is water: only 5% of the animal is really, meaningfully there. That part, at least, is relatable.

Turritopsis dohrnii was classified in 1883, 39 years before Kurt Vonnegut was born. As far as I know, Kurt Vonnegut never demonstrated much interest in jellyfish, so he probably didn’t have any personal contact with Turritopsis dohrnii. Even if he did, we didn’t know about its immortality at that point, only its existence. Turritopsis dohrnii was considered entirely unremarkable until 1988, when a marine biology student named Christian Sommer observed that the specimens in his care never died. Discovery isn’t always inventing; often, it’s observing something that has always existed. Even then, the extent of Turritopsis dohrnii’s regenerative abilities weren’t fully comprehended. It took until 1996 for scientists to start referring to the life cycle in terms of immortality. I was born a year later in 1997, and pretty soon after that all the other stuff started to happen, too. The jellyfish couldn’t have known. They don’t even know that we’ve started talking about them.

Turritopsis dohrnii can die, of course. They may not be limited by time, but they are beholden to the whims of the food chain. As noted, their defence mechanisms are limited by their size and non-complexity. Sea slugs in particular are fond of eating them. Time travel doesn’t work if you’re already being digested. They can recover from near-misses. Regeneration doesn’t just facilitate hypothetical immortality; it also allows physical trauma to be instantly forgotten. It turns out that if your body is an extracellular matrix then it does not, in fact, keep the score.

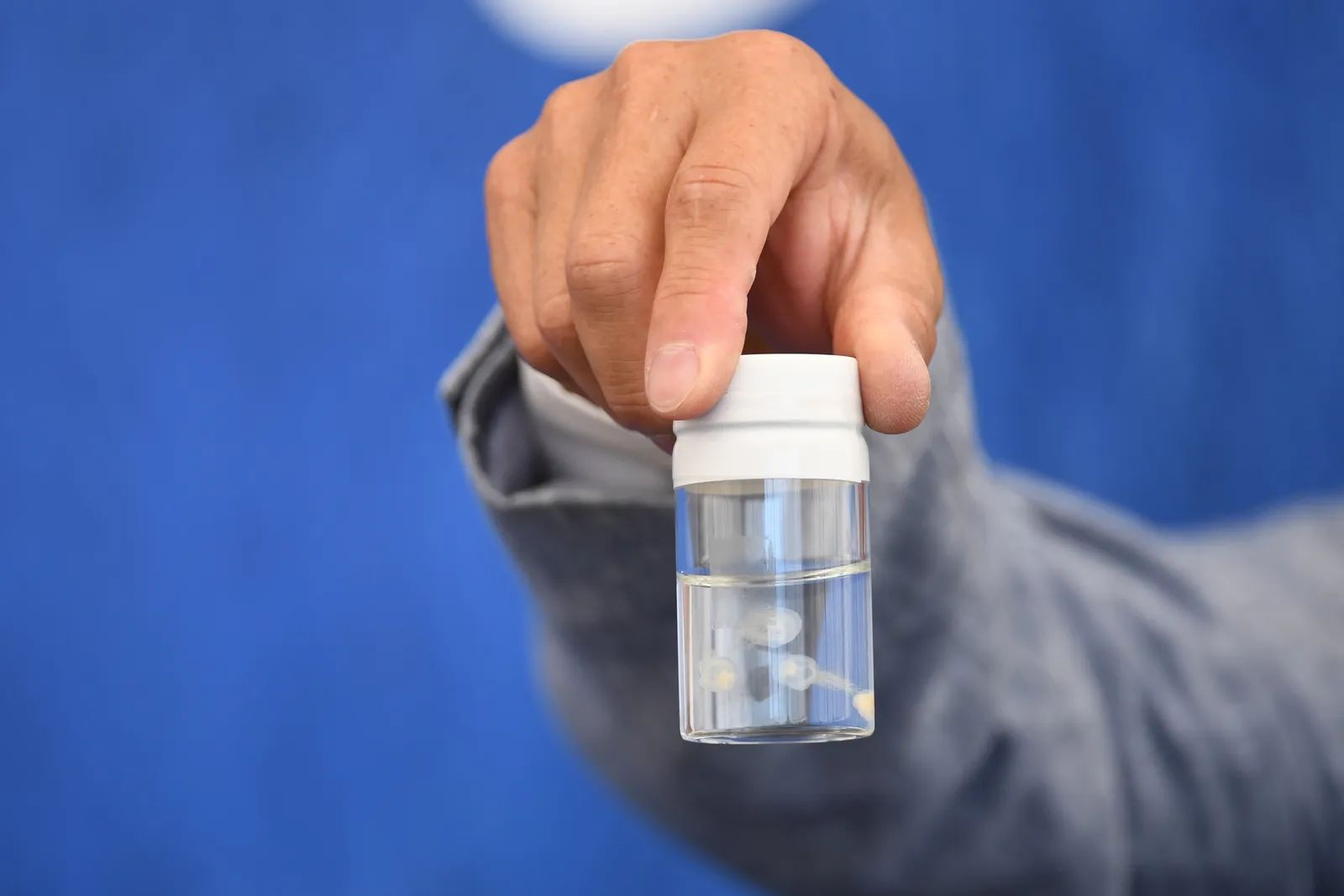

see how small a guy can be? (Ian Gavan, Getty Images)

Memory is tricky. For some things I have an exceptional memory: Pokémon, zoology, faces. Improved recall is common in certain kinds of autism. For other things, my memory is considerably worse. Dissociative amnesia is controversial due to its association with repressed memories, an idea that has been debunked and re-bunked by psychology for several decades now. Whatever your take on that aspect, it’s undeniable that trauma causes significant memory issues. I don’t remember much about my life before I was 18 or so, and even then things get spotty. I know they happened, and I could even tell you some events, but the full picture is missing. It is very difficult to form a cohesive sense of self when you don’t remember so much of your life. Unlike Turritopsis dohrnii, returning to the juvenile state is not regenerating. It’s the opposite, really. Memory doesn’t seem to be a problem that the jellyfish shares. The jellyfish doesn’t have to think, and it certainly doesn’t have to think about being anything other than a jellyfish.

As Vonnegut understood, time travel is disorienting. The past reappears in the present, unavoidable and overwhelming. For complex PTSD, it is many moments in the past at once, playing simultaneously, almost constantly. I struggle to respond appropriately to the present because I am five, and nine, and fifteen, and twenty, and none of those selves have ever known how to deal with what was happening to them, let alone when it’s happening all at once. A thousand televisions playing a thousand different moments on full volume simultaneously. I am sitting at the kitchen bench, but I am also on my parents’ kitchen floor, and I am hiding in the closet of my childhood bedroom, and I am watching my dog die in the yellowing backyard.

Listen: Mo Quirk has come unstuck in time.

I feel a particular kinship with Turritopsis dohrnii, despite the differences in our time travelling, my own inability to regenerate. Animals are easier to relate to than humans. The jellyfish, with its lack of nervous system and transparent body, is often easier to relate to than a person. Humans aren’t jellyfish, though. We have, for better or for worse, complex brains and long-standing memories. It’s the jellyfish’s lack of brain that allows it its immortality. If an organism has memories, it can never really revert back to its younger stage. It’s not just the body that changes. Time travel does not offer a clean slate.

When the jellyfish reverts, does it remember what it was? Does it remember close calls with predators, the impossible vastness of the passing whale? It can’t. It doesn’t have a brain. That’s the whole point. True reversion is only possible without remembering. This is why time travel is restricted to a simpler organism: any animal with a psyche could not stand it.

PTSD is not reversion, but inertia. The past loses its spot in line and emerges in the present, enormous and inescapable. I can’t say it better than Vonnegut did: I am unstuck. I envy the jellyfish’s non-complexity. The jellyfish’s backwards movement through time is regenerative, not destructive. It does not have to live with what those previous selves have survived. Human memory can’t start again, not really. Amnesia doesn’t work the way it does on screen. My memory has a lot of blank patches, but the atmosphere remains. I am trying to find some peace with it. It will take a long time, so I had better start now.

I find the notion of bio-hacking humans to be immortal to be tremendously dull. At best, it’s a pedestrian thought experiment. At worst, it’s billionaires wasting medical resources in the name of personally becoming the demiurge’s most special little boy. I can’t think of a less interesting goal. All the world around us, fossils and living things and things not yet known, and you want to spend your (yes, necessarily) limited time trying to stop your meat from decaying. Existence is a trade-off between rot and life. If you want to live forever, scoop out your brain and peel off your skin and dissolve your muscles in the tropical waters until you become see-through. For the rest of us, complexity means we must die.

Of course, the immortality imagined by transhumanist dipshits is very different to the immortality of Turritopsis dohrnii. They want an extension of linear life, not a reversion. The worldview that more closely resembles the jellyfish is reincarnation. I regretfully can’t find any material on whether or not jellyfish have been briefed on samsara. But still, it’s an imperfect comparison. The essence remains, but the ego does not. It’s a new start, not a true return to what has come before. The jellyfish remains in a category of its own.

Happily, I’m not the only one who feels a kinship with Turritopsis dohrnii. Since Sommer’s initial description of its life-cycle, scientists have found the jellyfish particularly difficult to cultivate in captivity. Only one researcher currently has a consistent captive population: Dr Shin Kubota, who lives and works in the Wakayama Prefecture. Kubota loves Turritopsis dohrnii. Of course he does. Finally, someone with some sense. We do diverge on certain things: he believes that Turritopsis dohrnii offers a new frontier for human immortality, which I will politely ignore. He also thinks they’re very cute, which I find much more agreeable. His devotion to his flock makes my chest hurt a little. He changes the water every day; he slices eggs into microscopic pieces; he takes his jellyfish with him when he travels to talk to other people about them. He writes songs about his jellyfish, which he often sings at conferences.

He hurts his jellyfish, too. It’s necessary for them to rejuvenate. It’s not necessary to hurt a human to make them rejuvenate, so there must have been some other reason for it.

Kubota believes humans can learn immortality from Turritopsis dohrnii, but it’s not simple. The spiritual requirements are, to him, bigger obstacles than the physical ones. In 2012, Dr Kubota told Nathaniel Rich for the New York Times Magazine that humans’ modern disconnection from nature limits our own ability to live. We are not, Kubota says, deserving of immortality. He doesn’t lionise the jellyfish, either. “They’re miracles of nature, but they’re not complete. They’re still organisms. They’re not holy. They’re not God.”

dr shin kubota tending to his great loves (Yoshikiko Ueda for the New York Times)

I’m so glad Dr Kubota exists. I take great comfort in knowing that I am not the only one so enamoured by animals. At the same time, I can’t share his enthusiasm for immortality. Time travel is exhausting enough. I find it hard to believe that humans can revert and retain ourselves. Certainly, when I am sent back I lose something. If we’re to learn something from Turritopsis dohrnii, I’m hesitant for it to be the ability to live indefinitely. Unlike the jellyfish, I will never lose myself completely. Like Vonnegut, like Billy, I am unstuck in time, but I still exist within it. There is a past, which I return to too often, and there is a future into which I am hurtling, perhaps not as linearly as most others, but still always, always moving, even now.