Giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) are uniquely unskilled at being alive. This makes them, if nothing else, immensely sympathetic. They are carnivores by biology, but at some point they turned against their natural inclinations in favour of bamboo, and only bamboo. Their gut still struggles to digest plants, and the lack of sustenance results in them spending most of their time asleep. Nor are they especially skilled at reproduction: scientists and zookeepers have a notoriously difficult time coaxing captive pandas to mate. Artificial insemination is common in captive breeding programs, while others have been known to show the bears “panda porn” to convince them to give it a go themselves. The conservation and repopulation of pandas has been front and centre of ecological justice efforts for decades. It is the chosen sign of the WWF (the animal people, not the wrestlers).

There is an argument that pandas are an erroneous focus for ecological restoration. Their cuteness is their main appeal; otherwise, it seems as though pandas have very little inclination to continue their species. In terms of attitude, the argument goes, pandas are a lost cause.

I subscribed to this view for a long time. I don’t know if I do now. I don’t like the implications of judging a disinclination for life as meaning a deserved death.

Pandas are more than just species to us; more than even symbols of the climate crisis. In the early modern era through to the early twentieth century, it was somewhat common for exotic animals to be used in diplomatic relations. In 1827, Muhammad Ali of Egypt sent giraffes to leaders in London, Austria and Paris. Zarafa, the Parisian giraffe, was famed for her elegance and beauty; her stuffed remains are currently on display in La Rochelle. In the early twentieth century, the question of animal ethics arose in Europe, leading to countless zoological parks undergoing significant public relations campaigns to rebrand from entertainment to education and conservation. Conditions of animal acquisitions by zoos improved steadily throughout the twentieth century; today, many zoos take a strong stance against exotic animal trafficking, the very activity on which they were originally founded.

The panda has a unique place in this history. The first recorded instance of “panda diplomacy” took place in 1941, during the second Sino-Japanese war. Pan-dee and Pan-dah (booooo) were gifted to the United States by Soong Mei-ling in gratitude for America’s aid during the Japanese invasion. Though the news saw significant attention at first, by the time the two bears arrived in the US, Pearl Habour had been bombed, and Pan-dee and Pan-dah were overshadowed by America’s entry into the Second World War. Through the 1950s to 1983, twenty-four pandas were gifted among nine nations by China. China’s relationship with the Soviet Union was deteriorating, leading them to seek out stronger relations with the US. In 1972, Mao Zedong gifted Richard Nixon two pandas, receiving two musk oxen in return.

In 1983, China halted its gifting of pandas to other nations; instead, they now offered the bears on a lease. As such, all pandas born after 1990 belong to China. The last non-Chinese panda is Xin Xin, who lives at Chapultepec Zoo in Mexico City. I’m not sure if Xin Xin knows about China. I’m not even certain she knows about Mexico. The only non-leased pandas given by China since the 1980s took place in 2007, when China gifted two bears to Hong Kong. I’m not sure if they understand special administrative regions either.

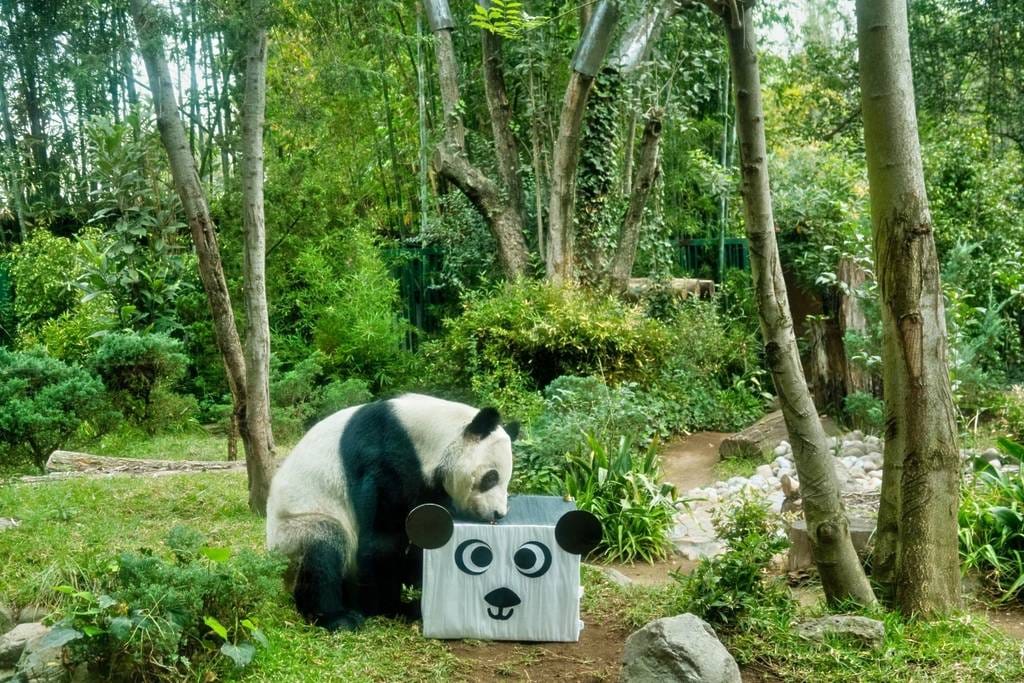

xin xin (left)

Panda diplomacy is, I suspect, a nightmare for pandas. They have never asked to be a symbol, they’ve never even asked for us to help them repopulate. All that we think of the panda is projection: aesthetic appeal, the problem of climate change, the notion of diplomacy. Pandas can barely be bothered to eat. I find it hard to believe they would be in favour of all this effort.

What else can we do, though? We can’t ask the pandas what they want. It’s tricky to ask people to commit to saving an animal that, by all accounts, does not want to be saved. Why aren’t pandas more grateful for what we’ve done to them? Why don’t they hate us more for what we’ve done to them? Someday, pandas will disappear. I’m not sure how soon that will be, only that eventually it will happen. We can’t always love a species enough to save it. I don’t know if we can love a species enough to let it die out. We can’t trust them to take care of themselves.

Conservation is often a matter of guilt. It is an attempt at reparations for what we have done to nature. This does not mean it is wrong, nor that it’s futile: merely that the motivation is strongly emotional. Pandas don’t seem to mind either way if they die out. We do, though. Is our comfort worth the pandas surviving? How much does that matter? The most recent estimates put the global panda population—captive and wild—at a little under 3000 individuals. That’s less than half the population of Summer Hill, where I currently live. Almost all of the currently extant pandas could sit in Sydney Town Hall, though I’m not sure they’d find the seats very comfortable. I don’t think pandas find being alive very comfortable in general. I feel the same way. It’s not up to us, though.